Digital Library

noun (countable) /ˈdɪd.ʒɪt.əl ˈlaɪbrəri/

an online place where books, documents and other texts written in dialects of Limburgish are digitally available to borrow or look at

Limburg portal of the DBNL

Some Limburgish literature is available on the Limburg Portal of the Digital Library of Dutch Literature of the Royal Library (DBNL). DBNL allows you to search for and download texts on your e-reader.

The Digital Library of the Limburgish Academy will be online in a few years. Currently, we are collecting Limburgish texts for the Limburgish Corpus. Our Digital Library will display literary texts. These will include original literature of Limburgish authors such as prose, poetry and plays. Also translations of e.g. Shakespeare’s ‘A Midsummer-night’s Dream’ (Ein ôngerstóng vôl touvering) and Lewis Carol’s ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’ (De Avventure vaan Alice in Woonderland) will be displayed.

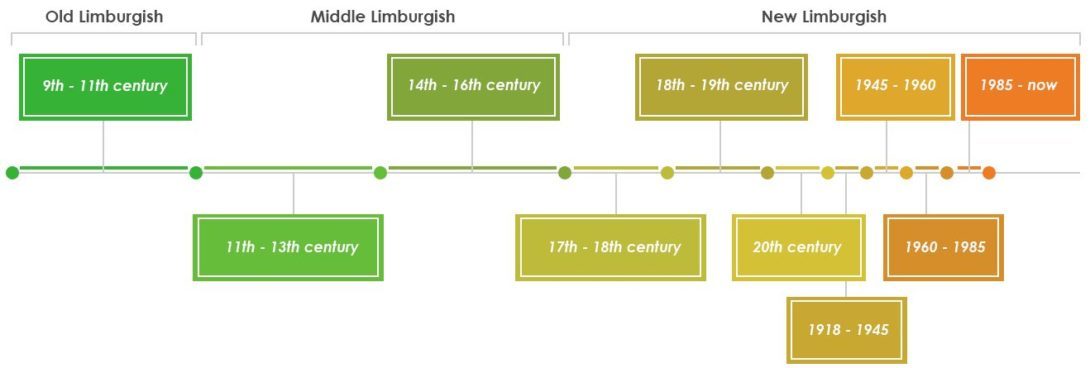

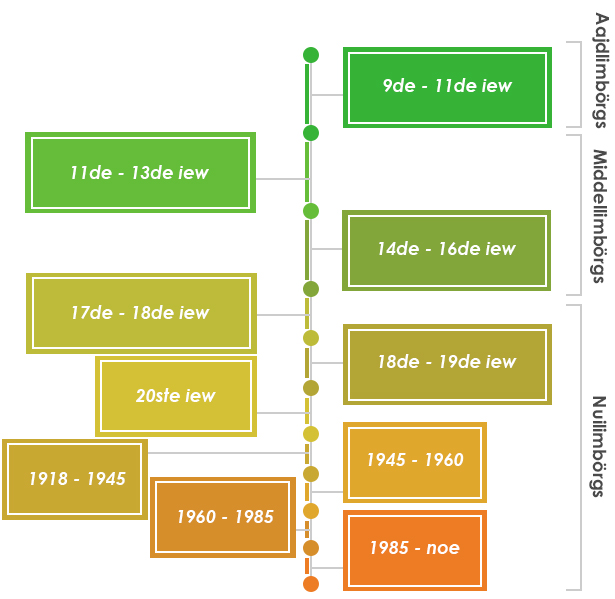

Limburgish has been used as a written language and in literature since the early Middle Ages. From the end of the 18th century, the various dialects were increasingly used in writing. A more detailed account is available in the Limburgish Literature History section.

Short overview of the Limburgish literary and writing tradition

Old Limburgish (9th-11th century)

From the 9th to 11th centuries, no literature has survived from the Meuse-Rhineland to which Limburg belongs. Only the Wachtendonck Codex (± 900) offers a larger text continuum. Above these Latin psalms, a literal translation of the words is written in the native language. The Latin order of the words has been maintained and therefore no conclusions can be drawn about sentence structure.

Middle Limburgish (11th-16th century)

11th-13th centuries

The Limburgish Meuse-Rhineland was one of the most important European literary landscapes in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. This was not because of its own innovative performance. From Romance cultures important narrative motifs were passed on to the neighboring Germanic language regions in the east. Monasteries were important centers of the production of written works. They often produced religiously or contemplatively inspired texts. Private individuals also sometimes wrote texts, focused on the characteristics of their lives or the Limburg Maasland.

Texts were written in different languages, often Latin, but also in Middle Limburgish. The Limburgish written language probably does not fully reflect the vernacular of the time, but often reflected a more Brabantic or Dutch written language.

Henric van Veldeke‘s work is well known. As one of the few medieval troubadours, Veldeke wrote lyricism in addition to epic. Veldeke’s ‘Eneas’ novel (1170-1190), a song about the courtly and amorous lover Tristan, and the Saint Servaas legend (± 1220) with more than 6000 verses are some texts that have been passed on. His work is mainly known from later copies, written in Dutch or German dialects. There are also fragments of Middle Limburgish works by unknown authors. The ‘Trierse Floyris’ novel (± 1200) tells the love story of Floyris and Blancheflor, the grandparents of Charlemagne, who was himself a literary motif of the Meuse-Rhine region. Sint-Brandan’s journey is a miracle story, probably also from the twelfth century.

The Middle Limburgish writing tradition has survived after Veldeke. Although few texts are known, a charter from the Bishop of Liège of 1202 shows that all books suspected of heresy toward the Holy Scripture were confiscated. It is very clearly indicated that this also includes books in the Germanic vernacular, so what is now Limburgish.

The ‘Limburgish Aiol’ (1220) dates from the thirteenth century. It is an epic text that tells one of the many stories of Emperor Charlemagne. Fragments of Limburgish professional language or the language of scientific tracts come from North Limburg in the form of the so-called ‘Limburgish Health Rules’ (1253). These were written on the margins of a Latin calendar. The ‘Nederrijns Moraalboek’ (1270-1290) is an anthology of moralisations, considerations and quotes from learned authorities. There are also fragments of crusader and romance novels, songs and poems and hagiographies.

14th-16th centuries

The ‘Limburgish Sermons’ (± 1300) are a collection of 48 handwritten sermons and tracts that were once part of five hundred manuscripts and early printed works. These Sermons include the ‘Maastricht Passion Play’. In the 14th and 15th centuries, translations of legends of saints’ lives in the vernacular came from the area around Maastricht, Maaseik and Venray. The 15th century produced a ‘Limburgish Prayer Book’ from North Limburg and from Tongeren about ten songs. Passed on from the 16th century are prayers from the Maaseik Agneten Monastery and songbooks such as the Venlo-Gelders Huisboek and the Venlo-Gelder Song collection. The Venlo-Gelders Huisboek is also a source of love poetry. Petrus Treckpoel (1442-1508) wrote a Chronyk der Landen van Overmaas at the beginning of the 16th century, chronicling the region’s history starting during the Old Testament period and ending with observations on contemporary regional political relations.

New Limburgish (17th-21st century)

17th-18th century

From the turbulent 17th and 18th centuries a lot fewer literary texts are known than from the preceding centuries. Writings are often of a personal nature; people wanted to record important personal matters and (historical) events.

Only some small literature by Jacob Kritzraedt (1602-1672) from Gangelt, across the border from Sittard in the Rhineland, is known. Kritzraedt wrote two occasional poems in the form of anagrams at the end of 1640: Get lang and Land genug.

18th-19th century

At the end of the 18th century, writing in Limburgish was stirring again. In the beginning, these writings are mainly occasional texts, such as poems, small stories and songs. Literary works and plays only started to be written from the second half of the 19th century onwards.

The Sermoen euver de wäörd Inter omnes Linguas nulla Mosa Trajestensi prastantior gehauwe in Mestreech 1729 (±1770) is an anonymous declamation that focuses on foreign influences on the native language. Ludovic Pascal Delruelle (1735-1807) was a parish priest for the Wyckse St.-Martinus parish in Maastricht. For his reproach poems he found inspiration in conversations or insults that he overheard from his window of the parsonage in the street below. Pieter Gilles Schols (1768-1847), Paul Lenaerts (1777-1836) and Andries Piron (born 1804) wrote poems or songs in the Limburgish dialect of Maastricht.

The late 18th and early 19th centuries produce more works written in Limburgish. In folk almanacs such as Den Opregten Antwerpschen Almanach and Den Opregten Maastrichtsen Almanach, stories, poems and songs are published in the Limburgish of Maastricht. They are written for a less literate audience and contain mainly folk motifs.

In 1806, at the request of the French Ministry of the Interior in the Meuse-Rhineland, ‘The Prodigal Son’ from chapter 15 of the Gospel of Luke was translated into the vernacular. This to determine in which regions French was the vernacular of the population. For many Limburg dialects, these are the earliest texts from the New Limburgish era. In the nineteenth century The Prodigal Son would prove to be a popular translation text for language research and was translated into many different Limburgish dialects. In 1836, a fragment of a text by Erasmus was also translated into the Limburgish dialect of Weert for language research.

Theodoor Weustenraad (1805-1849) wrote his witty and satirical poem De Percessie vaan Sjerpenheuvel between 1830 and 1840. His epic poem appeared to be too controversial for its time, due to its portrayal of the hypocrisy of the Catholic Church and many affluent families in Maastricht and his candid descriptions of sex. It was not until 1931 that the entire text was published anonymously by a group of young intellectuals, especially Charles Nypels, with illustrations by Charles Eyck. In 1964 Harie Derks republished it to provoke the bourgeois spirit in Limburg. Lou Spronck published a new, more scientific edition in 1994, with illustrations by Toussaint Essers and one in 2009 as part of his thesis.

During the second half of the 19th century, French or German plays were played in Limburg at the literary societies of Momus in Maastricht and d’n Dramatiek in Roermond. In addition to these translations, original works were created, amongst others in the Limburgish dialects of Maastricht, Roermond and Heerlen. In 1889, the novel Oet de Fransentied in Mecklenbórg narrated in the Limburgish dialect of Roermond was published as serial in the newspaper De Nieuwe Koerier. The translator is unknown. As far as is known, this is the longest text in Limburgish from the 19th century.

20th century

At the beginning of the twentieth century, in the aftermath of the 19th century tradition, Fons Olterdissen (1865-1923) wrote comic operas. The two best known ones are De Kaptein van Köpenick (1907) and Trijn de Begijn (1910). Olterdissen also wrote folk stories called Vaan stad en lui veur 50 jaor (‘Of the city and the people 50 years ago’), a petite histoire of daily life in Maastricht between 1860-1870.

The voice of Jules Frère (1881-1937) breaks the silence in West-Limburg that spanned the entire 19th century. After returning from a devastating experience during the war years 1915-1917, he wrote his first and only collection of poems Druvig Bukske, an ode to his native Old Tongeren.

1918-1945

After the First World War, stories and poems appear, especially in various magazines or newspapers. Books are only written by exception. Themes are: the Limburgish identity, chauvinism, religion and the past. Many of the authors are clergy, which probably contributed to the fact that these texts are quite tame and moralistic.

Edmond Franquinet (1896-1974) conforms less to the prevailing literary motifs. In 1927 he published a book with Dadaist-inspired stories called Maskeraad.

New theater in Limburg came from Frans Schleiden (1896-1955). His plays such as D’r brand va Bellent (1931) and De Koel i Lutterendal (1930) were performed until well after the Second World War. Many local theater companies such as the Zuid-Limburgsch-Toneel (ZLT) and A.K.D.IJ. from Spaubeek, specialized in original and translated Limburgish language plays.

1945-1960

During the difficult time of post-war reconstruction between 1945 and 1960, Limburg slipped into a conservative Catholicism. After the war, the work of Bèr Hollewijn (1907-1978) was staged throughout Limburg by the theater company De Kemediespeulers. His work is based on Catholic teaching and tries to present those doctrines on a wide range of subjects in a realistic and understandable way for a general audience, in order to combat ways of thinking that were seen as wrong.

After 1954, the Speelgroep Geleen also performed about twenty performances of original Limburgish-language plays by Hub Janssen and Sjef Nijsten, among others. Max de Bruin also produced translations of works by Wilfried Wroost, Frans Streicher and Erhard Asmus.

Felix Rutten (1882-1971) was already a well-known and leading author in Dutch between 1900 and 1940, when he started using his Limburgish from Sittard for his literary work. In addition to Catholicism and the good life of the past, Rutten uses neo-romantic themes. His work includes the Christmas story Daags veur Krismes (1957), Novellen (1959) and an anthology of his Limburgish-language work Doe bleefs in mich (1971) published posthumously.

1960-1985

The ’68s were Limburg writers who opposed the conservative Roman tradition. Although the homeland, history and Catholic faith did not disappear completely, the door was opened to a wider range of themes. More books were published and the language itself received attention.

In 1976 Veldeke published an anthology called Mosalect, with poems and prose pieces by writers from all over Limburg. It showed how widely Limburgish literature was produced.

Paul van der Goor (1932-1983) is a poet and writer, known for a collection of 16 poems Tösse Vreug- en naojaor (1977). He is one of the first to write about themes outside of Limburg, such as his experience of a raid in Amsterdam during the occupation of World War II.

Léon Veugen (1919-2001) is the author of the first fully-fledged New Limburgish novel. In 1980 he published his novel ‘ne Zöch van de Ieuwigheid (‘A Sigh of Eternity’). A theme of journeying home, based on a Homeric example, the experience of sexuality and dealing with faith outside the framework of the Catholic Church are innovative and taboo-breaking themes.

More works were also translated. Jan Wouters translated Van de Vos Reinard (1963) and Ederein (‘Everyman’). Fons Vossen translated several sonnets of Shakespeare (1976) and his ‘A Midsummer-night’s Dream’ as Ein ôngerstóng vôl touvering (1982).

1986-now

The generation of ’68s has initiated the further maturation of Limburgish literature. After Léon Veugen, the door was open for full-fledged Limburgish novels, which would now be written by several Limburgish authors.

Jac. Linssen‘s (1922) novel Leef en leid in vreuger-jaore (‘Love and Sorrow in Earlier Times’) (1996) recounts the struggle faced by the residents of Maasbracht in 1918 during the difficult times of the Spanish flu epidemic. In 2003, Jo Cobben (1938) wrote a novel De drie èngele van Aelse (‘The Three Angels of Elsloo’) in which three angels assess the influence of the new age.

Ger Bertholet (1948) is an actor, writer, poet, singer and translator of plays, often under the pseudonym of Zjèr Rapaille. His book Sjweitberg (1999) contains a selection of his weekly columns. Bertholet discusses subjects such as contraceptives, eroticism, workers’ suffering, and World War II. In addition, he published poetry and wrote the theater monologues like Knötsj and Puen d’r Vuurmond.

Wim Kuipers (Maasniel 1939) writes poetry and stories in Dutch and Limburgish. His publications include Moeles en sjaelevaeger (1999), Platlandj, gedichten uit Neel (2000) and Kaoleries (2002).

At the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first the Limburgish language was increasingly used for literature by a growing number of Limburgish authors. Joep Leerssen, Raymond Clement, Frits Criens, Jeanne Alsters-van der Hor, Colla Bemelmans and Toos Schoenmakers-Visschers are some of the names of writers who write about various subjects. More works have also been translated, including Oet ‘t Fabelbook vaan Aesop (‘Aesop’s Fables’) (2011), De Avventure vaan Alice in Woonderland (Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’) (2012) and fifty poems by Konstantinos Kavafis (2019) by Yuri Michielsen.